There Will Be More Elizabeth Holmeses

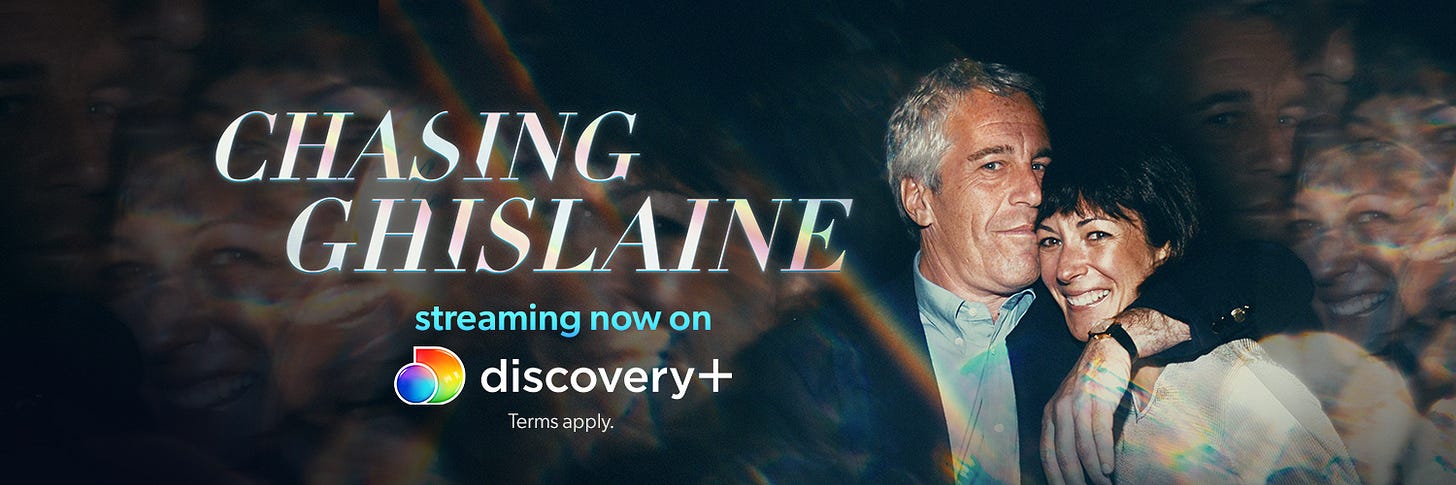

One of the unexpected surprises and joys of reporting on Ghislaine Maxwell and Jeffrey Epstein has been the extraordinary women I met in the courtroom and others who reached out to me in response to the podcast or the discovery+ docuseries.

Hillery Nye is one of those women. She is a veteran business attorney with over twenty-five years of experience representing a range of tech companies from start-ups to institutional clients, including Microsoft, Amazon, Intel, and Paramount Pictures Digital. She is also an angel investor and adjunct professor of privacy and technology law at Seattle University School of Law. Throughout her career, she has had to handle difficult ethical issues—some of which resulted in the firing of execs and others in her being “invited to pursue her excellence elsewhere.” She’s also a whistleblower who has been fired for honesty. (The latter is just one of the chilling stories she and I will be getting into in the near future, both on a podcast and here.)

Hillery emailed me back in September that the personal aspect of my Audible original podcast “Chasing Ghislaine” had touched a nerve:

Frankly, I wept when I heard your personal story. It hit home. (How many conversations have I had—just like yours with that fella Jeff—which left me feeling vaguely violated?) I, too, am a mother of two boys, each just entering into the world as young adults. I, too, have been through a difficult divorce… Perhaps more importantly and more honestly (and humiliating and terrible): I’ve had to compromise more than I am willing to admit to be successful in my career. You have started a conversation that needs to be continued.

I wanted to get her take on Elizabeth Holmes, who was convicted earlier this month on four counts of fraud as the CEO of the health-tech start-up Theranos, which, for over a decade, was hailed in the media as a unicorn up there with Apple. Until that is, thanks to several whistleblowers, it was revealed that the Theranos technology—by which a pinprick of your blood was supposed to quickly reveal all sorts of biometrics—did not work.

Elizabeth Holme at the Forbes Under 30 Summit in Philadelphia, PA on October 5, 2015. || Gilbert Carrasquillo/Getty Images

My conversation with Hillery has been condensed for clarity.

VICKY: So, your thoughts on the trial?

HILLERY: The evidence that the prosecutors put before the jury was rather shocking because it's so familiar. Entrepreneurs don’t sell products; they sell stories, hope, and hype. It is not surprising that many cross the line into outright deception, especially when that line is ill-defined and there is so little transparency into this world of privately funded enterprise. Perhaps the only thing that was truly surprising was that the person on trial was female. Frankly, for every Ms. Holmes, there are thousands of men out there doing the same damn thing—or at least something perilously close to it. I think the only difference here is that Ms. Holmes’s product was more than an iPhone app or an online service; she was selling a health product that threatened the health and safety of its users and raised real issues of consumer protection. Plus, let’s face it: she had a scandal-worthy story: Scandal, sex, corporate intrigue, and an attractive, highly educated woman who's been hyped up by presidents and professors and highly regarded executives as the next Steve Jobs. In some ways, Holmes had amassed power and prestige in the same manner as Jeffrey Epstein (minus, of course, the ugly bits about child abuse and extortion). If you look at their enablers, they’re not dissimilar. They surround themselves with the powerful to create a patina of credibility and prestige. I think there's going to be a lot of folks who are divided about whether or not this really makes a difference in the start-up community. I think the only tangible difference is going to be that nobody's going to hire a kid of an investor, or grandson of an investor, ever again. That’s only funny because it’s true.

VICKY: You are referring to Tyler Schultz, [the grandson of former U.S. Secretary of State George Schultz, who was a Theranos board member]. Tyler was one of the whistleblowers.

HILLERY: Yes. From my perspective, the topic that has been undervalued is the whistleblowing component of Ms. Holmes’s case. As somebody who has experienced the real-world challenges associated with being a whistleblower (personally and professionally), I can say that this part of the Theranos story is the most phenomenal. In my experience, most whistleblowers get fired. And the firing creates an environment of corporate silence that perpetuates bad choices. Here, however, you have whistleblowers who were, ultimately, in a unique position to be heard.

VICKY: So, lack of transparency is the norm in the start-up world?

HILLERY: The start-up world is generally a closed ecosystem. If things go off the rails—if the technology does not work, the customer does not buy, or the revenue projections don’t reflect reality—no one is particularly surprised. What entrepreneurs do with that failure, however, is what often separates the ethical from the fraudulent. Ethical entrepreneurs disclose, pivot, fix, regroup and/or reorganize. Fraudulent entrepreneurs cover up and misrepresent. There is a vast middle ground, however, between the two extremes.

I could see somebody like an Elizabeth Holmes going in with the best of intentions…but slowly getting into the business of deceit. A deletion here; a revised report there. Fudged numbers that no one seems to notice or care about in this private island of entrepreneurship. So it snowballs.

In order to successfully start a company, you have to sell a vision of the future. You have to sell a dream, and you have to be good at the salesmanship. There's this well-known trope in the start-up world—“fake it until you make it”—and, of course, the famous Steve Jobs concept of “the reality distortion field.” So there is a general acceptance that founders are fundamentally salespeople who will make big promises that they likely cannot fully deliver.

What's hard is when the fundamental premise for the start-up’s very existence fails. What do you do when the thing doesn't work, when fundamental assumptions fail, when the deal that was critical for the success of your venture falls through… and when you need to raise more money?

VICKY: Surely in the real world, if the product fails, the company goes bust or stops?

HILLERY: No, that's not true. In fact, that's the pivot—that's the infamous pivot. I remember talking to one VC who said he's routinely surprised by something revealed by a portfolio company in the first post-investment board meeting. Savvy investors expect a certain level of salesmanship and recognize that not all has not been revealed to an investor or board member. And that revelation can happen at any time, not just at the onset of the relationship between the start-up and the investment community.

Throughout that relationship, however, the investor expects less salesmanship and more transparency. When things do not go as planned and an investor faces losing an initial investment, there is a tendency for the entrepreneur to re-up the salesmanship, however, and for the investor to have a greater desire to believe the pitch. At this juncture, the difference between deception and salesmanship is critical—and it is often a very fine line. Failure is often redefined by the start-up as “part of the learning curve,” “an opportunity to course-correct,” a “response to unexpected market forces,” “an impetus to refine the model, the product, the technology, the team etc.” If you are an investor, you want to believe that. In fact, you have a vested interest in the start-up turning things around. The company may not be that magical unicorn, but there is still a desire to get some sort of return on investment. So you are much more inclined to continue to believe, to fund and not just walk away.

Often, if the company is in trouble, the founders will say so. And, in a perfect world, that means the board will get more active, and, for example, they will start looking more deeply into the organization and the product the company is trying to build or monetize. I have to wonder about the Elizabeth Holmes scenario, however. If she had asked for meaningful engagement from her investors, would they have been capable of providing it? Frankly, although her board was comprised of well-educated and respected people, none had a meaningful background in biotech.VICKY: You mean because Holmes’s board was notoriously comprised of famous power players including Henry Kissinger [former United States Secretary of State], James Mattis [now-former Secretary of Defense], the aforementioned George Shultz [former United States Secretary of State], Richard Kovacevich [former CEO of Wells Fargo], and William Perry [former United States Secretary of Defense]?

HILLERY: Yes. Frankly, Ms. Holmes did not have biotech companies really backing her, so nobody was asking the right questions of her or the organization. I think that gave her a broad playing ground, if you will, and plenty of opportunity to smooth the rough edges of the truth, such that—over time—none was left at all.

VICKY: Are you saying it wasn’t all her fault? Was she treated fairly or unfairly by the jury?

HILLERY: I think Ms. Holmes was treated fairly and got what she deserved. But I also think she certainly was treated differently than most start-up founders. She got both the benefit and the burden of that disparity. In the beginning, as a well-heeled, educated, and beautiful blonde, she was given unprecedented access to the wealthy, the powerful, and the prestigious—and the press—all of whom she manipulated to serve her needs. But, in the end, her well-known contacts and reputation made her the perfect villain.

VICKY: Will her example change behavior in the start-up world?

HILLERY: Investors are not spending more time avoiding the Holmeses of this world; in fact, they are spending less. That could signal a bubble that's going to burst. More has changed over the past two years in the entrepreneurial world than in the past twenty. Even five years ago, there was no such thing as “letter-down financing,” “pre-seed investment”—or even the use of the word “FOMO” [Fear of Missing Out] among seasoned investors. And in the rush to be first, to avoid FOMO, there is less investor scrutiny and more opportunities for entrepreneurs to cross ethical lines. Ultimately, this could result in a crash…

If that happens, remember you read it here first…

As Elizabeth was crashing in 2017, I was just emerging as a female tech start-up founder. The impact of her failures, deceit, manipulation and inflated valuation became an filter through which VC's would see female founders seeking any funding.

I became obsessed with her story, trying to make sure it did not become mine as I ventured into the world of big tech start-up. In fact, her story and approach to business, in a way, became my own personal "how not to" instruction manual for navigating this big crazy world of start-ups.

Looking forward to more conversations!

I am quite surprised to read a college dropout described as well educated.