Omicron and the Jury + Who, Really, is Ghislaine Maxwell?

Dispatches from the Ghislaine Maxwell Trial

While the jury in the Maxwell trial has deliberated for the last couple of days, we journalists sat in the court room or in the corridors, read paperback books, and chatted—but not for too long, given that two of our number went down with Covid. So, too, apparently did that of the courthouse cleaning staff. Everyone is aware of the irony that Omicron has the potential to up-end all orderliness at the end of a trial that has been notable for its pace and order.

Judge Nathan has told everyone they must wear KN95 masks when the jury reconvenes today for what will be a short week. (Court is only sitting Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday of this week.) One wonders, based on the notes coming out of the jury room, if the jury will even reach a verdict this week. I have my doubts.

Given the requests for transcripts of testimony (first from Jane, Carolyn and Annie and then, on the second full day of deliberations, from Kate and Juan Alessi), it seems clear the jurists are taking their role seriously—and, thus, they are in no rush. When Judge Nathan offered them the option to deliberate Thursday, the foreperson wrote back “No, thank you. Jurors have made plans for tomorrow.”

Holiday schedules notwithstanding, when this jury was picked, they each agreed to sit not through just this week, but next. This was supposed to be a six-week trial. So they will have already cleared their calendars and informed their bosses of their unavailability through the first week of January.

But what happens if the variant becomes the driving factor that changes priorities for the jurors? What happens if one of them falls sick? The alternate jurors have not been released by the judge—but just imagine the chaos that would ensue if an alternate now had to enter that jury room. First, there would likely be almighty argument between Maxwell’s defense team and prosecutors over which alternates should be selected (each side has carefully selected their jurors), and, second, deliberations would basically have to start all over again. With every passing second increasing the likelihood of complications, the chance even of a mistrial is far from impossible.

Meanwhile, what of Ghislaine Maxwell? She has now spent her 60th birthday—on Christmas Day—in prison.

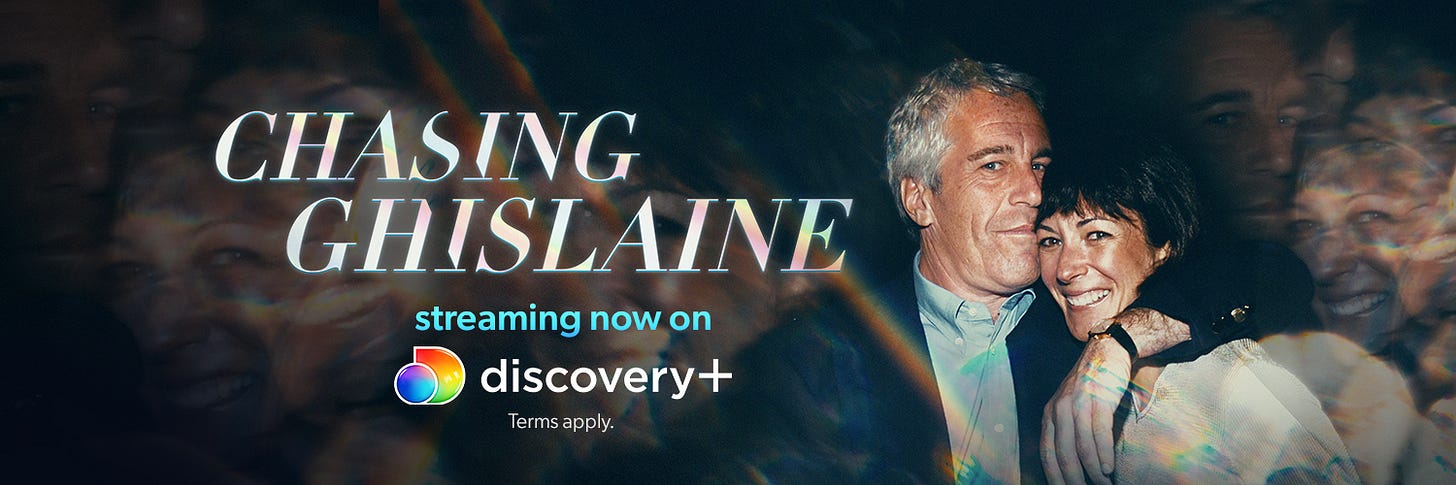

Ghislaine Maxwell, circa 2000. || Mathieu Polak / Getty

Over the past few weeks, it’s remarkable how extraordinarily composed Maxwell has appeared to be while sitting a room during a trial that could send to her to jail for many years.

Maxwell has displayed no obvious emotion at any of the testimony, which has been, at turns, both heart- and gut-wrenching. She has been amiable with her lawyers and other supporters, who consist of family, lawyers and legal assistants in the first two rows behind her. And when her lawyers have left the room, she has turned round and stared at everyone else in the courtoom, sketching us at times in a move that has been thoroughly disarming.

Maxwell takes copious notes and passes them at the end of each day to lawyer Leah Saffian, who sits with the Maxwell siblings (and, some say, was reportedly behind those infamous In-N-Out Burger photos). Then Saffian passes them on to Kevin Maxwell, Ghislaine’s brother, who is clearly the defacto “head” of the Maxwell family. The implication of this is that Kevin then brainstorms with the lawyers, relaying Ghislaine’s comments.

Kevin, I’ve been told for the last 18 months, is the “quarter-back” of the defense. But, to me, the current messaging is clear: if he’s the quarter-back, Ghislaine is the coach.

It’s a masterful performance. At the most vulnerable moment of her life, somehow Ghislaine Maxwell looks as though she’s in charge of this script.

However the verdict does eventually come down, the frustration of this trial is that we still don’t really know who the real Ghislaine Maxwell is. We don’t know what we’d find if we could peel back all the layers of the onion and ask, “What really happened between you and Jeffrey Epstein? What really happened after your father died? What really happened when your father was alive?”

We don’t know why Epstein wired $30 million into accounts associated with Maxwell’s name. Prosecutors told jurors to “use your common sense” when thinking about that sum:

“Your common sense tells you that you don't give someone $30 million unless they're giving you exactly what you want, and what Epstein wanted was to touch underage girls. When Maxwell took that money, she knew what it was for and now you do, too. It was payment for committing terrible crimes with Jeffrey Epstein.”

Thirty million is a huge figure by any standard. So of course the theories I’ve always heard—about Epstein being the conduit who hid Robert Maxwell’s money after the tycoon’s death and disgrace in 1991—are doing the rounds. (The Maxwell family has always said there was no hidden money and that any stories of that sort are pure myth.)

We also don’t know what came first: Epstein’s sexual abuse of minors or Maxwell’s presence in his life. And, to me, this is the biggest question of all.

The trial largely operated under the given assumption that Epstein was always a depraved person and that he roped Maxwell in to delivering children to satisfy his perverted sexual whims. This was made quite clear by the timeline of the indictment and by the lack of questions probing at any alternate history for Epstein.

And yet, in all of my reporting, I’ve never encountered anybody who noticed anything strange about Epstein’s sexual preferences until the 1990s—i.e., when Maxwell was around.

My sources told me that, in the 1980s, Epstein liked young-ish women, but they were not underage. In fact, we heard testimony from former Miss Sweden Eva Andersson-Dubin, who testified she had dated Epstein on and off for eight years, starting at age 21 or 22.

So, what happened?

Stuart Pivar, an art dealer and former great friend of Epstein’s who told me he cried when he heard about Epstein’s death, told me that Maxwell and Epstein had embarked on a “folie à deux.”

What did Pivar mean by this?

Pivar said that Maxwell is “misunderstood.” That she came from Europe—and a different set of morals.

I had heard during my reporting that Maxwell was wild sexually. And she was proud of that. It was her trademark. In the 1990s, Maxwell reportedly started holding dinners during which a woman gave fellatio lessons; at the time, this was deemed so culturally revolutionary that the then-deputy editor of Marie Claire magazine commissioned an article about it, although everything except the instructor’s name was kept under a pseudonym.

Maxwell’s male peers also seemed rapt by her ribald ways. “How fun to stay up late at night talking about sex with Ghislaine Maxwell,” I remembered a British man telling me.

What I heard from sources was that the reasons she was seen as “cool” was because she was thought to be in charge of her sexuality. She was so confident about it. Nobody I ever spoke with considered that there might be dark desperation behind it—certainly not a controlling man.

I remember asking Maxwell about Annie Farmer’s allegations about a topless massage when Farmer was only 16.

Back in 2002, Ghislaine told me she was “horrified” that I’d mention an allegation like that, from a “stranger.” How would she have time to give anyone massages? (Her defense said during her trial that Maxwell did give the massage but it was not sexualized. Any contact with Farmer’s breasts was because it was a massage of Farmer’s pectoral muscles, the lawyers said.)

That’s the person—the outraged woman who, the defense wants you to believe, has been ruined because of a poor choice of boyfriend, “the biggest mistake of her life”—who has been on show in the court room.

My gut, based on my reporting, tells me the real story is a lot more complicated.

And, whichever way this trial goes, we may never get to learn it.