My Mother

A Remembrance

Last night my mother passed away.

She was 84. And she’d been bedridden with dementia for years. She’d declined ever since had a mini stroke at 71, which in itself was flabbergasting, because nobody took greater care of herself than my mother. She exercised; she hardly drank; she took a shelf-full of “supplements” at breakfast. And when she went on vacation she brought All-Bran cereal with her, which both amused and irritated the heck out of my twin sisters and me.

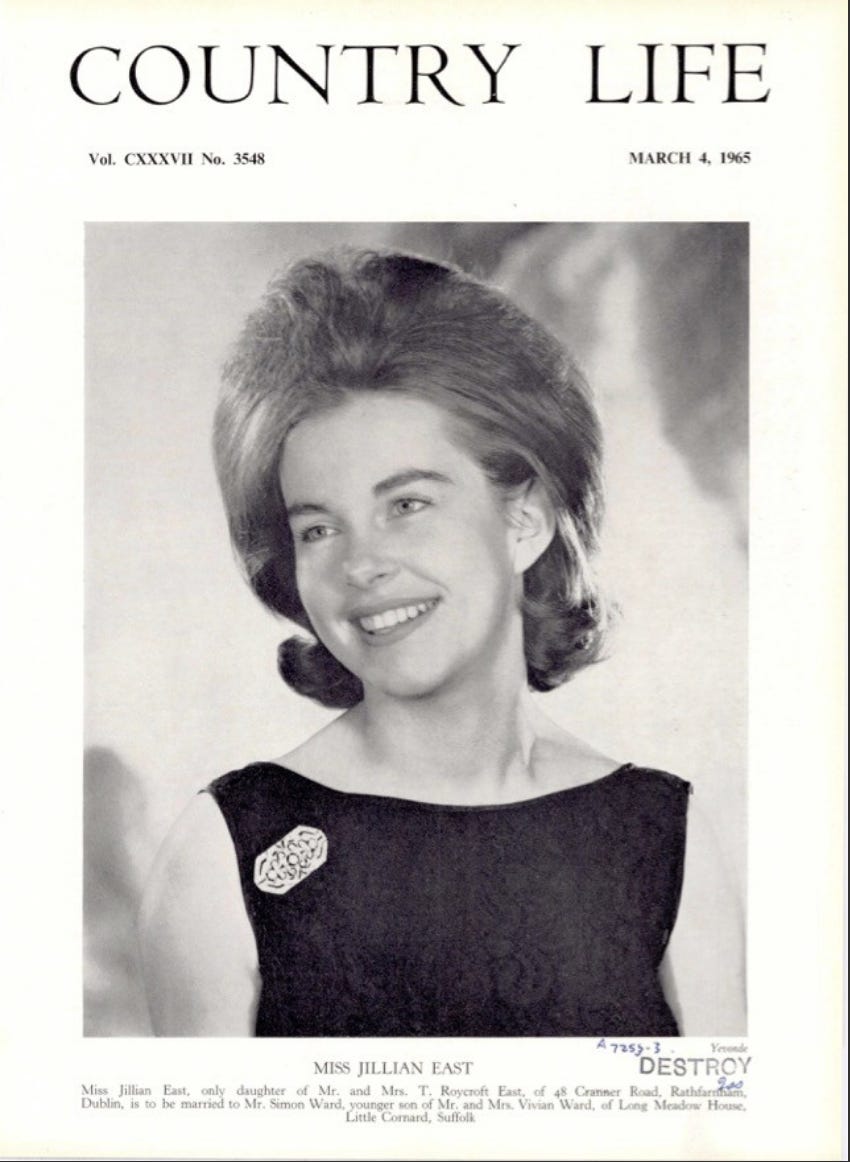

Yes, she was healthy, but we suspected that vanity was the chief propulsion behind all this. She had good reason to be vain. Our mother was extraordinarily beautiful; when she entered a room, people stopped talking and stared. We even stopped talking and stared. I remember thinking one night as I watched her lacquer her hair, and spritz her perfume, that no matter how hard I tried in life - and I am a trier - I would never be able to physically compete with my mother.

She knew this, too, and was forever making “suggestions” which I took extremely seriously. She told me to breathe through my nose and not my mouth; and for a while she stuck a clothes peg on my nose at night to straighten it; she told me never to underestimate the value of effort with one’s appearance. To that end she bought her three teenage daughters each a set of electric carmen rollers, instructing us to wave our dead straight hair before we presented ourselves anywhere, including at our All Girls boarding school; she clocked our weight when we came home; and she had strong opinions about our clothes. I’d love to tell you that we rebelled, but we didn’t.

We just tried harder to follow her lead.

My mother did not endorse coming second. In anything. She taught us to read long before other kids could even talk properly. When my sister Lucinda, aged four, one day felt like skimping a reading session, my mother pointed out of the window to where a garbage truck was parked, and its driver was hauling the liners from our bins.

“If you don’t work hard in school, you will end up marrying that man,” she told my sister. We stared out of the window, trying to visualize such a fate. That we might not depend on a husband for our destiny was not something that was discussed. Our mother was a product of her time and she raised us to dazzle the opposite sex with our accomplishments.

She drove us miles to attend ballet classes; ballroom dancing classes; to attend Scottish dancing classes; we had a tennis pro hit with us every single day and we were partnered with the best boys in the county for the local tennis tournaments, which we almost always won. We had piano lessons, recorder lessons, voice lessons. On weekends we were tested when listening to classical music playing on Radio Three. We had to guess the composer of whatever was playing - and we learned to guess right. We were sent to cookery school; to ski school; to the Berlitz language school. We were sent to Italy, to France, to Germany. We were sent OUT to meet people she thought we ought to know.

She taught us to drink milk before going to parties where they served alcohol, and to drink water when we came home from them. She told us never to drink anything stronger than white wine before dinner. She taught us to include everyone at the table in dinner conversation and the importance of being “rounded.”

“He’s very nice but…..” was her catchphrase we dreaded when we introduced boyfriends to her. There was always a but. When the man I married first came home, she said “he’s very nice…but he talks about “business” too much. My mother considered that very dreary. To be amusing, in her book, one needed to be cultured.

She, herself, was always amusing. My father thought she was the most fascinating person he’d ever met. At Christmas time, we’d do the round of parties in the county, all crammed into my dad’s SUV. My mother would always get into the passenger seat last, swathed in an enormous fur coat, and my father would speed off too fast into the dark and the English country lanes. Somehow, they always filled the air with talk. The most fun would be on the way back, where replenished with too much champagne they dissected every person and every conversation topic that had been had in the previous two hours. You can be sure we heard the phase “Well, so and so is very nice….but”….

There was always a But.

Being a perfectionist takes a toll. I know that now firsthand. I knew it secondhand as I watched my mother struggle with getting older. She was blessed genetically and remained remarkably youthful looking right up to the day she had her stroke. In her sixties, she still commanded the attention of everyone when she walked into a room.

But the world had evolved without her. Women, including her daughters, wanted to do more with their lives than just marry and entertain and my mother was suddenly less certain about the purpose of her extraordinary drive.

“I think she decided she needed to compete with us,” my sister Lucinda said to me today. Lucinda is right.

I became a writer. So, my mother became a writer. Of sorts. She clipped so many newspaper articles that her pretty bedroom started to resemble the clippings library at News International where I worked for a while. We weren’t sure what all the clippings were for, exactly. But we knew better than to query whatever was going on. She wrote manually, draft after draft after draft. My father would come home from work in London and typed up with two fingers whatever the latest script said. Typing was not something my mother considered she should do.

She did get published. Once. In the Independent. She phoned all her friends and told them to read it. The subject matter of the article - her mental health struggles and her diagnosis with Seasonal Affective Disorder - was almost besides the point, although it was a brave and pioneering thing to write at the time. The point, for her, was that she was published. She was somebody.

She pushed my father to dream. “I think you should take up shooting,” she said. So, he did. “I think we should go to Russia,” she said. So, they did. “I think I’ll go to India,” she said. And she did. Every year. With her girlfriends. My father was entirely bereft without her.

When she heard I was expecting twin boys, she suggested I name them “Lancelot” and “Constantine.” She was not joking. She was deadly serious. “They need to start life, standing out.”

My mother stood out. She was funny (often without meaning to be). When we went on safari to Africa, she kept us all waiting in the jeep at dawn because she was eating her AllBran and applying her lipstick. “Who are you applying the lipstick for? The lions?” I asked her. She ignored me.

Before she was put in a nursing home, and while my father was still pretending he could look after her without help, she was sectioned. My father had gone on an errand and she’d wandered into the street in a nightgown. An ambulance had come and picked her up, because someone deemed (rightly) she was not safe walking around by herself.

My mother was not someone who was going to let other people define who she was, even then. She started sweet talking the psychiatrists and the nurses with one purpose in mind: an exit. “Don’t you worry, I’ve got this,” she said to me through gritted teeth on the phone. “You’ll see I’ll be out of here in no time.”

She did get out. But she couldn’t stop the damage the stroke had done to her brain.

I’m not going to think of my mother the past few years, lying in a bed in a nursing home. I’m going to remember my mother as she meant me to remember her.

I’m going to remember her entering our living room for a party, dressed sensationally, and pausing for effect in the doorway, a smile on her face, appreciative of her awed audience.

She was beautiful then. And she’s beautiful now.

Rest In Peace, Mummy.

Outstanding piece. Beautifully written. Well done! My condolences. sb.

She had an enormous impact on you. Your compassion for Epstein’s victims in particular.